UNDER THE ARC

Also in this edition-

From the Archive: Midwives to the Purposes of God

Poem of the Week: ‘STILL’

News: Beach Baptisms in Ouistreham, Amazing Women

What do you do with the bible when you have an important decision to make? Play bible Bingo (open at random, run your finger down the page until you find something useful…)? Recall your Greatest Hits and Best Bits (go back to the verses that have guided you in the past…)? Surf the Translations (keep trying different versions until you find one that tells you what you want to hear…)? The techniques are endless, and all are useful at least some of the time – but there is another, less tried technique that offers a surprising level of help. It is simple to explain, but its execution takes hard work and commitment. It is this: know the story that the bible is telling.

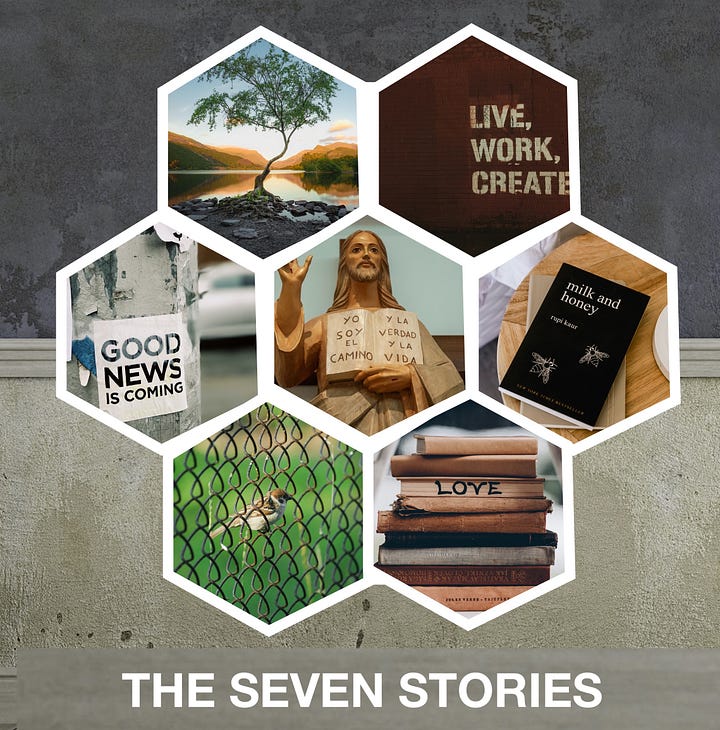

Like any work of literature the bible has an overarching narrative, a beginning, middle and end that make sense of the story’s individual elements. This ‘big story’ can be summed up in a number of ways – the journey from a garden to a city; the story of creation, fall and redemption; the history of who we are, where we are, what’s wrong and how we can fix it. The common thread in all of these approaches is that they take seriously the narrative flow from the beginning to the end of scripture: they allow the bible’s overall shape to inform an understanding of its component parts. Like the picture on a jigsaw box or a recipe card, this sense of an underlying story helps us to see where each part fits and what each ingredient is there for.

Not everyone agrees that the bible has a single storyline. After all, it is not even a book. It is a library made up of 66 books created by multiple authors over many centuries and in a range of cultural and historical settings – and written in three different languages. How could such a diverse collection of writings even tell one story? There are a number of good reasons for believing that it does. For a start, it is a deeply human story. It’s different authors had many distinct views of what they were writing and why, but all believed that they were saying something important about the human condition. The very fact that these diverse texts were collected and preserved, and have been treated with honour over successive generations, tells us that their readers, too, have received them as something more than workaday scribblings. They are marked by the sense they carry of a higher purpose. Then there is the fact they they all seek to tell the story of God. Monotheism runs through the bible like Blackpool through a stick of rock. There is one God, maker of all things, and this is what we know about him. Again, the perspectives are many and varied, the angles constantly changing, but they are uniform in the subject they address: these are writings about the world’s creator. For those who suggest that the multiplicity of authors and origins militates against there being a single narrative, the surprise is that the reverse is true. It is precisely because all these diverse arrows point in the same direction – defining, by their directionality, the same unseen reality – that we know there is a story here to be found.

It is also significant that the bible itself refers to a beginning, a middle and an end. This is not to suggest that the order in which the texts are presented to us is the order in which they were written. When we read a story that begins in Genesis and winds its way through Old Testament history to lead us into the Gospels, the letters and the climax in John’s Revelation, the temptation is to believe that this is how the events themselves unfolded, but this is an error, and an unhelpful one at that. Many of the New testament letters, for example, were in circulation before any Gospel was written – Gospel texts are as likely to be a reflection on the letters as the reverse – and there are Old Testament texts that predate Genesis by quite some margin. The story itself, though, does follow a clear narrative pattern, and is defined by it’s beginning in the creation of all things and its end in their restoration. Just as the Christians of the early centuries formulated creeds to make sense of their beliefs, so we are right to find ourselves in this story – to know that we live between this beginning and this end. As a range of authors, over many centuries, reflected on their perception and experience of the one creator God, this is the story they chose to tell – this is what they believed to be true. We are under no pressure to agree with them, but if we trust them, and accept as credible their witness, we too will anchor ourselves in this epic narrative.

In the end, of course, to trust in the story the bible tells is an act of faith. Our beliefs – that there is one God, maker of all things; that he has revealed himself to honest seekers over successive generation and that he is uniquely revealed in the person of Jesus of Nazareth – cannot be proved by the text but must be brought to it. It is when we accept that the God who formed Adam, called Abraham, appeared to Moses and became flesh in Jesus is the one God maker of all things that we begin to see more clearly the threads unifying diverse biblical texts.

How is this useful to us, though? How does a sense of the shape of the biblical epic help us to understand its individual texts? There are a number of important answers, and they all revolve around the character and nature of God. When Moses meets God in a unique bushfire, he learns for the first time the maker’s name – “I am that I am”. The Hebrew includes the sense of “I will be that I will be” and one way of interpreting this is to see it as a promise: “wherever God is being God, God will be the God that God is.” It is this consistency; this faithfulness in character and nature that gives the bible its unique flavour: and it is against this promise that we are asked to interpret God’s actions, in scripture and in our own lives.

The overarching narrative of scripture tells us who God is; what he has done in the past and what he plans to do in the future – all of which aid us in understanding what he might be doing in the present. When I pray for healing and am not healed. When my society or culture develops in a direction that is antithetical to my faith. When I’m seeking guidance in vocation; in relationships; in emotional health. When I’m seeking to develop strategy for a small church with scant resources living as a minority in a hostile environment – or, by contrast, when we have achieved growth and success and are given wealth and power. In these and other areas it is vital to have a sense of who God is and what he is doing – and this can only come from knowing the story we find ourselves in.

The danger, of course, is that in any one of these situations we can cherry-pick favoured verses, cut them from their context in the story and paste them over the cracks and fissures in our lives. We can proof-text healing or its absence; opposition or favour; success and failure; why God does want me to take that promotion and why he might not. One of the glorious strengths of the scriptures – also their implicit weakness – is that they offer a verse for every occasion. Even the words of Jesus can be edited to support entirely opposite responses to the same situation. “Sell all your possessions and give the money to the poor” and “You will always have the poor among you” (Matt 19:21; 26:11 NLT) can both be used to support a particular response to economics and justice. I have seen these exact texts weaponised by left and right to score political points, yet both are Jesus. Both, in fact, are red-letter moments.

The answer to this dilemma is to let the big picture of God’s work in the world inform our understanding of his will in particular situations – to let the bible’s overarching narrative interpret, for us, its specific verses. When you step back to see the beginning, middle and end of the story, how does your perception of its individual parts change? Reading Jesus in the light Eden; setting the ideas of Paul against those of Abraham; asking where we might be right now in the story if John’s vision of its ultimate end is to be trusted – all these are actions of letting the macro inform the micro.

The frustration here, at a very practical level, is that all too little is done, in many of our churches, to explore the overarching narrative of scripture. We are too fixated on the forensic analysis of individual texts – often in support of our particular preferences and prejudices – or we substitute our own two dimensional summaries for the richness of the world’s greatest story. “I was a sinner heading for hell but Jesus died so that I can go to heaven,” for example, has elements of biblical truth to it – but isn’t the story the bible tells. There is a breadth, a wonder and yes, a mystery, to the narrative of scripture to which our simplistic presentations do no justice.

I have four suggestions as to how we might address this concern.

-

Firstly, make it a goal to come to a deeper understanding of the overall story the Bible is telling. If you have the opportunity to influence the teaching programme of your church community, nudge them in this direction. Seek-out resources that empower you to grasp this overarching narrative. One resources I have no hesitation in recommending is The Bible Project, a website, video series and podcast exploring the many themes that make-up the bible’s story. Egalement disponible en français.

-

Secondly, let the macro shape your understanding of the micro. When you are looking to interpret a specific verse or passage, ask what its place might be in this drama. How does this passage move forward the purposes of God?

-

Thirdly, do the same with your engagement with events in your own world and time. How does it help you, in present circumstances, to know that wherever God is being God, God will be the God that God is?

-

Lastly, anchor your faith and practice in this knowledge of the character and nature of God. Let the bible’s many micro-stories build like a mosaic to a portrait of the maker of all things, and let that picture be your guide.

Live under the arc of God’s purposes in the world – aware of his actions in the past and sure of his intentions for the future: find your story in the story of God.

Image: https://unsplash.com/@spacex

FROM THE ARCHIVE: Midwives to the Purposes of God

“The woman we honored today held no public office, she wasn’t a wealthy woman, didn’t appear in the society pages. And yet when the history of this country is written, it is this small, quiet woman whose name will be remembered long after the names of senators and presidents have been forgotten.”

These words were spoken in 2005 by then Senator Barack Obama, at the Detroit funeral of Rosa Parks. Fifty years earlier, a forty-two-year-old Parks had altered the course of American history through a single act of civil disobedience: refusing to give up her seat to a white man on a city bus in Montgomery, Alabama. Her arrest triggered a 381-day boycott of the bus system led by the Revd Martin Luther King Jr. This may not have been the birth of the Civil Rights Movement, but it was its coming-out party. “The world knows of Rosa Parks”, former President Bill Clinton said, also at the funeral, “because of a single, simple act of dignity and courage that struck a lethal blow to the foundations of legal bigotry.”History books are written in honour of those (often men) who stand on the world’s stage. They all too easily forget those (often women) who got them there.

Witness, for example, the story of Shiphrah and Puah. These two women are among the least known on the Bible’s long cast list, and yet their role is crucial. Shiphrah and Puah were midwives, in charge of births across the Hebrew slave community. Their story is told in the first chapter of the book of Exodus and centres on a single verse: “Because the midwives feared God, they refused to obey the king’s orders.” (Exodus 1:17 NLT) Their act of disobedience ushered in a whole new chapter in God’s mission. They are midwives to the plans of their maker. A power-hungry Egyptian king determined to limit the number of Hebrews born in his country commanded the midwives to murder at birth all the male children. They chose to disobey this law of terror, tricking Pharaoh into believing that they couldn’t get to the mothers in time. As a result of their courage three things happened: the Hebrew race grew; Moses was born safely; and God blessed his two faithful midwives.

Like Parks and King centuries later, Shiphrah and Puah engaged in a sustained plan of civil disobedience that struck, in their own context, “a lethal blow to the foundations of legal bigotry.” They played a vital part in the unfolding plans of God, not by taking centre stage but by carrying out their day job with diligence and justice and by finding the courage to defy an unjust law. They are an abiding model for all who see life not as a journey into fame and fortune but as an opportunity for faithfulness to the purposes of God. Here are three key principles active in the lives of these lionhearted women.

1. The Midwifery Principle – In Exodus 1 the story of God’s mission in the world is taking a new turn. Moses is about to come to prominence, and with him a whole new chapter of God’s purposes will be written. There will be a shift from family to nation; a new emphasis on justice; an unfolding of God’s plans for community and worship. All these things, though, depend on the turn being made – and the hinge is in the faithfulness of these two women. In pursuing a path of obedience (to God) matched with disobedience (to injustice), Shiphrah and Puah take their place in history. They are used by God to usher in a whole new era. By their breadth of vision and submission to the ways of God, they “deliver the deliverer” of Israel. What higher calling could there be?

2. The Principle of Long-Haul Blessings – We know very little about Shiphrah and Puah beyond this one courageous decision, but we are told that the blessing of God went with them. “Because the midwives feared God,” Exodus tells us, “he gave them families of their own.” (Exodus 1:21 NLT) One interpretation of this draws on the traditional view that midwives in the ancient world were often women who could not themselves have children. Their act of supporting young mothers was a kindness extended at the cost of great personal pain. Whether this is true or not, the clear implication here is that for these women there was blessing to be found in serving others. A literal translation would be that God “gave them households”. He established them, extending to them the very blessings they were helping others to enjoy.

3. The Unexpected Joys of Obscurity – Do you love others in the hope that you’ll get a good blog post out of the experience? Are you hoping to be noticed, building your own career on the backs of those you “serve”? I know you want to say “no,” but I know, too, that the answer is too often “yes.” It has been for me, on many occasions. You and I share a tendency to practise righteousness “in front of others, to be seen by them.” (Matt 6:1 NIV) How insightful of Jesus to warn us of such a danger two thousand years before Facebook even existed. Grace calls us to a deeper way. It is the way of hiddenness, a road on which, away from any spotlight, we act out our love for our maker and for our neighbour before the eyes of God alone. Our reward is the good that it does us; the growth we experience; the joy of intimacy with God – and the vicarious pleasure of holding someone else’s baby and knowing that “I helped bring this into the world…” Do you sense the call of God to embrace such obscurity?

Women in both Egyptian and Hebrew families were socially powerless. They had no property rights, and in effect were property. They had no political clout, and were not taken seriously in either religious or societal debate. Their place was in the home with the children, while their men met at the City Gate, or in the Temple, or at the royal court, to transact the really important deals. But God is not fazed by human convention. Our notions of who is significant mean nothing to him. He slips under the fences of our self-importance and sows seeds of redemption. While we look for the spotlight, he works at the margins. While our eyes are fixed centre stage, he hovers gently in the wings. The exodus is a narrative set in patriarchal times and with a generally patriarchal spin to its story. The good guys and the bad guys are for the most part just that: guys. The God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, who called Moses and Aaron to lead the people in a confrontation with Pharaoh, his magicians, and his army shows little sign of running an equal opportunities policy, and the Hebrew culture created post-exodus was male-dominated to a fault. But look again. The very fact that Moses is available as a masculine hero role model is down to the bravery, tenacity, kindness, and faith of a whole series of women. The Hebrew midwives are the first to subvert Pharaoh’s regime, risking their own lives in disobedience, but they are just the start. Moses’ mother, unnamed in the text, applies courage and creativity in a complex plot to preserve her son’s life. A sister – presumably Miriam – is then recruited to oversee the plan. And finally Pharaoh’s daughter herself becomes involved, showing compassion and mercy and risking the wrath of her father. In a time when the prophets are silent and no man speaks for the slave people, it is women who keep the dream of God alive. The same pattern is repeated in the New Testament, where it is the receptive faith of Elizabeth and her young cousin Mary that opens the way for the incarnation. If we rush too quickly past these miracles, past these women of faith risking their very lives, we will end up with a story of salvation that is not only male-dominated but is also incomplete and skewed. The fact that just such a narrative holds sway in some of our churches goes to show how poorly we read our own history.

From Gerard Kelly, The Seven Stories that Shape Your Life, Lion Hudson, 2017 (pp. 101-105)

Image: Matt Walsh https://unsplash.com/@two_tees

POEM OF THE WEEK: ‘Still’

When all is still

And sabbath-slow

Action abated

Distractions dismissed

There is a silence so deep

Even God does not speak.

In quiet companionship

Partnering with peace

My speechless soul mate

Saying nothing

Tells me everything

I need to hear

GERARD KELLY, A World Still Turning, CHAMINE PRESS, 2020

NEWS: Ocean Baptisms at Ouistreham

On a bright but chilly Sunday in October, we gathered on the beach at Ouistreham for the first ever baptism service for our Caen Vineyard congregation. With as many guests from beyond the church as from within it, the day was encouraging, uplifting and full of joy – and the beginning of what we hope will become a bi-annual event. It is thrilling to see the steady growth of our community in Caen: an eclectic mix of French nationals and ‘etrangers’ with a wide range of ages represented, and a genuine hunger to engage. We are small and we are new… but a Jesus Revolution 2.0 has begun.

NEWS: Amazing Women

We’ve also been having an excellent time in our community bible study, meeting some of the amazing women of the New Testament. Ever since researching for the original Seven Stories book, we’ve been aware of the pivotal roles played by women in the unfolding of God’s purposes in the world. Despite the intrinsic patriarchy of the society into which Jesus was born – and the subsequent misogyny witnessed in many of our churches – the Christian faith has at its heart a radical message for women: of inclusion, empowerment and visibility. We’re working hard, in our small corner, to ensure that women’s voices are heard.

Leave a comment