Will We Ever Burn Out On Beauty?

I have an op-ed in the new Vogue Business package on “The Future of Appearance” today, all about whether we’ll ever “burn out” on beauty. Click here to read it in full, or scroll down for an excerpt.

Beauty today is an exercise in exhaustion.

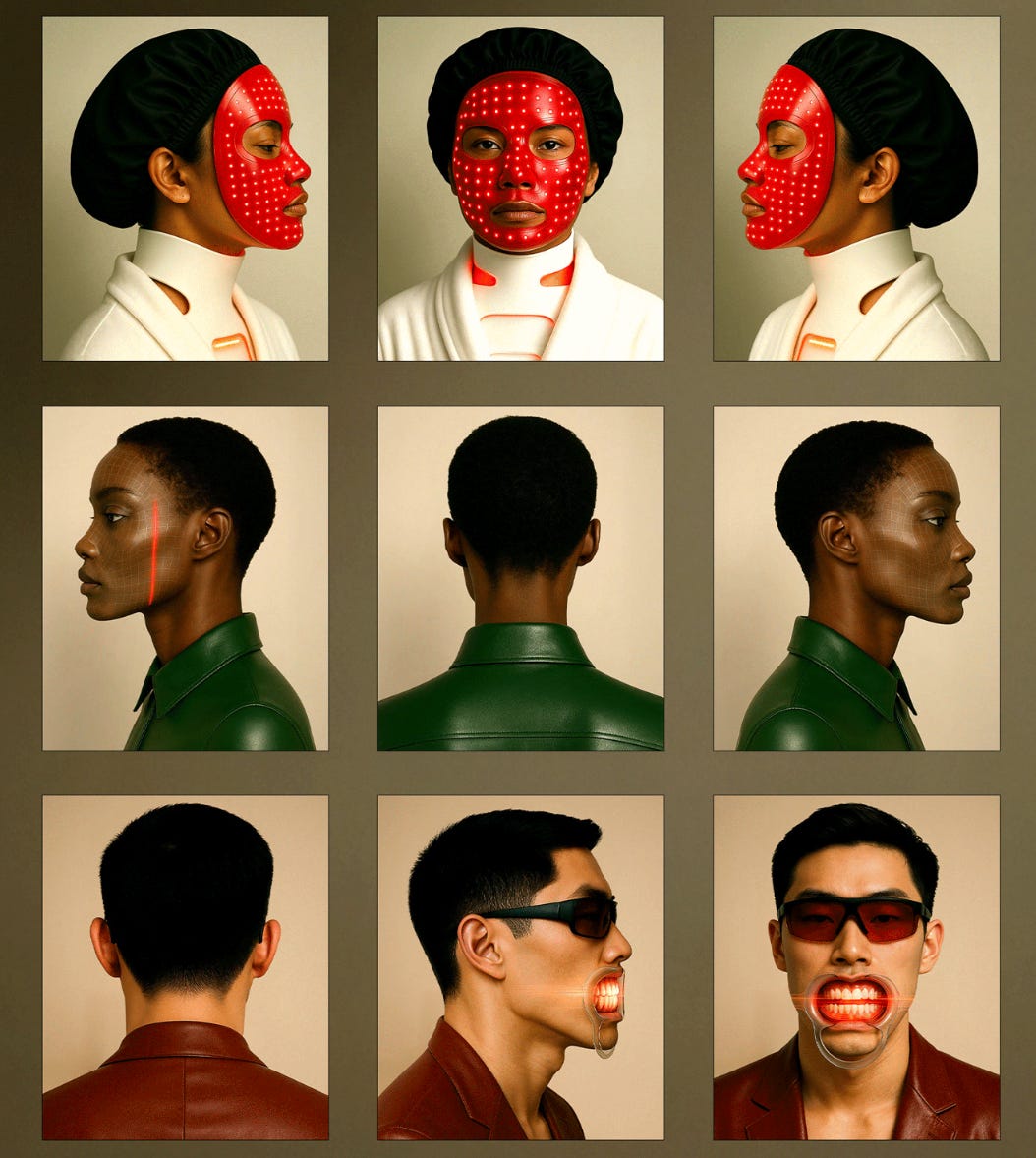

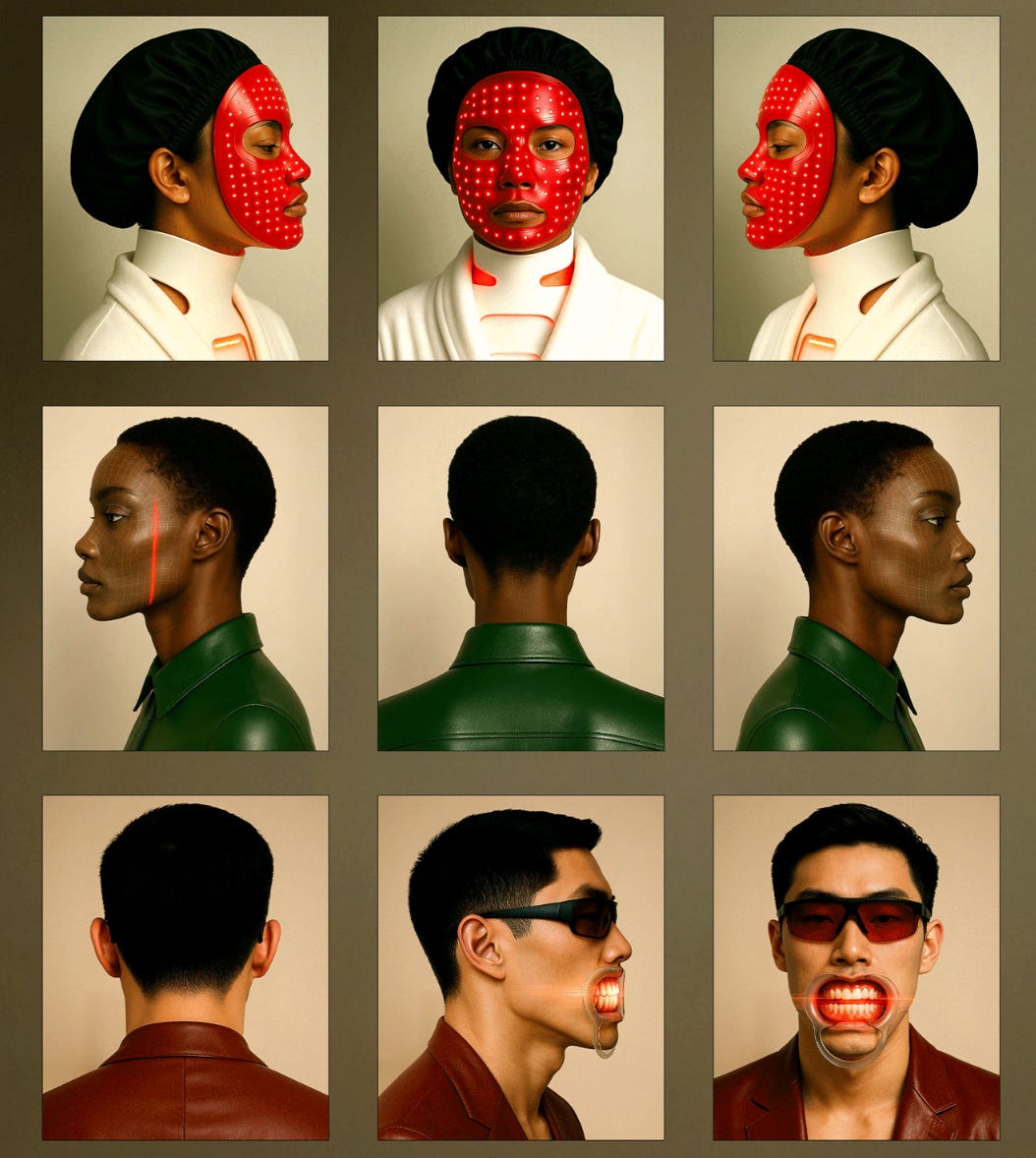

The reigning regimen is “high maintenance to be low maintenance”, which celebrates the effort it takes to appear effortless: semi-permanent eyebrow and lip colour tattoos, eyelash tints and lifts, red light therapy sessions, microcurrent facial massages. The ‘morning shed’ — or the performative removal of overnight skincare treatments, including face tape, mouth tape, sheet masks, eye masks, peel-off lip tints and heatless curlers — has turned getting ready into garbage collecting.

Tweens have anti-ageing routines. Grandmothers are getting ‘glamma makeovers’. Somewhere in the middle, a 38-year-old is spending $140,000 on a preventative face lift. Non-surgical procedures — Botox, filler — increased nearly 58 per cent between 2019 and 2023, per the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, a figure that continues to climb; upkeep requires multiple appointments per year, whether patients prefer the cartoonish excess of ‘Mar-a-Lago face’ or the invisibilised labour of the ‘undetectable’ look. Veneers are trending. Weight loss drugs are trending. ‘Chestnut teddy bronde’ highlights are trending. Everyone on TikTok is chugging collagen supplements, or hair growth supplements, or sleep supplements, or gut supplements. Some of them are using tooth gloss — that’s “lip gloss for your teeth”. Doritos makes nail polish now. President Trump sells perfume. It seems there is no surface left to smooth (Dr Paul Jarrod Frank recently promoted a treatment for back wrinkles) and no innovation that doesn’t already exist (see: hole serum).

“Beauty has become such a time-consuming and immersive part of people’s lives over the past decade,” says Zeynab Mohamed, industry reporter and author of the

newsletter. “It’s almost incomparable.”

Lately, Mohamed is seeing signs of overwhelm in both herself and her wider beauty community. “The smallest steps in my routine can often feel like a huge task,” she admits. Some influencers — tired of performing beauty, then performing that performance for an online audience — are starting to leave the profession entirely. “I would say 100 per cent of my time, energy and brain space, as well as 30 or 40 per cent of my income, was dedicated to the pursuit of wellness and beauty,” says

, former influencer and author of forthcoming memoir If You Don’t Like This, I Will Die.

Recent works of fiction reflect this feeling of frustration. Aesthetica, a 2022 novel by Allie Rowbottom, imagines a cosmetic procedure to reverse all previous work. The Substance, the 2024 film starring Demi Moore, treats the industry’s most enduring promises — better, younger, perfect — as fodder for body horror.

Could it all portend the end? Are we headed for a beauty burnout?

Industry executives are wondering the same, particularly since trend forecaster WGSN has predicted the Great Exhaustion, a fog of fatigue that will condense and descend upon us all in 2026. (Has it not already?) This collective feeling, it says, will be fuelled by countless and concurrent global crises: climate change and income inequality; life online and the widening political divide; chronic health issues and skyrocketing healthcare costs; artificial intelligence anxiety and job insecurity; the unending deaths of ongoing war; and the rollback of basic human rights for women, the LGBTQ+ community and people of colour. The firm has circulated a report to help brands navigate potential pain points, but in my opinion, Big Beauty will be just fine.

I have a theory that the average beauty routine expands in direct proportion to political upheaval. Call it the Aesthetic Index.

The Great Recession of 2007 and the 2008 financial crisis coincided with the arrival of Keeping Up With The Kardashians, as the ‘five-minute face’ of the early noughties gradually gave way to the more elaborate Kardashian base — foundation, concealer, powder, highlighter, contour, bronzer, blush.

Following the 2016 election of President Donald Trump, and into the pandemic, skincare was rebranded as selfcare — an act of “political warfare”, in the selectively repurposed words of late activist Audre Lorde — and quickly became the industry’s fastest-growing sector, driving 45 per cent of its growth the next year. Searches for 10-step skincare (cleanser, toner, essence, exfoliant, oil, serum, spot treatment, SPF, moisturiser, mask) surged in the middle of Trump’s first term, and ‘meta face’ emerged near the end of it. The uncanny aesthetic was modelled after Instagram filters, as well as the platform’s photo-editing technology, and brought to life with $17,000 of non-surgical interventions per person per year, according to one 2019 estimation.

In 2020, the year of Covid, people “hyper-fixated” on beauty, says Brooke Devard, host of ‘The Naked Beauty’ podcast. “My listenership exploded during the pandemic,” she says. Hours on Zoom triggered the Botox boom, and plastic surgery saw similar growth, as procedure rates climbed 19 per cent over the following two years.

The Supreme Court overturned Roe v Wade in 2022, and this formal subjugation of American women was met with casual objectification — glazed donut skin was the trend of the year. In 2023, as over a dozen states enacted near-total abortion bans, consumers reclaimed body autonomy where they could, as they aspired to look like Barbie and injected off-label Ozempic. Multi-state attacks on transgender rights juxtaposed the girlhood craze, a sort of retail therapy in the form of pink lip gloss and bow-shaped barrettes.

When Trump was elected again in 2024, one woman told The Telegraph she spent big at the Sephora sale “to cope”. The extensive routines that define 2025 (see above) don’t exist in spite of the political chaos, but because of it.

In this way, each factor of the Great Exhaustion will also fuel the beauty industry.

Continue Reading on Vogue Business

The rest of the essay includes:

-

Specifics on how the pain points of the Great Exhaustions will be used to market cosmetic products

-

Exhaustion as “a set of symptoms for beauty brands to solve”

-

The relationship between economic inflation and aesthetic inflation

-

Beauty as a bid for survival (ex: “I am disabled and autistic and consider beauty labour part of masking,” says one anonymous respondent in a survey I conducted on beauty standards and quality of life. “If I were to show up in professional settings the way I exist at home — unkempt, bare faced, plainly ill and exhausted — my disability would be visible, and my job in danger.”)

-

& more!

Continue Reading on Vogue Business