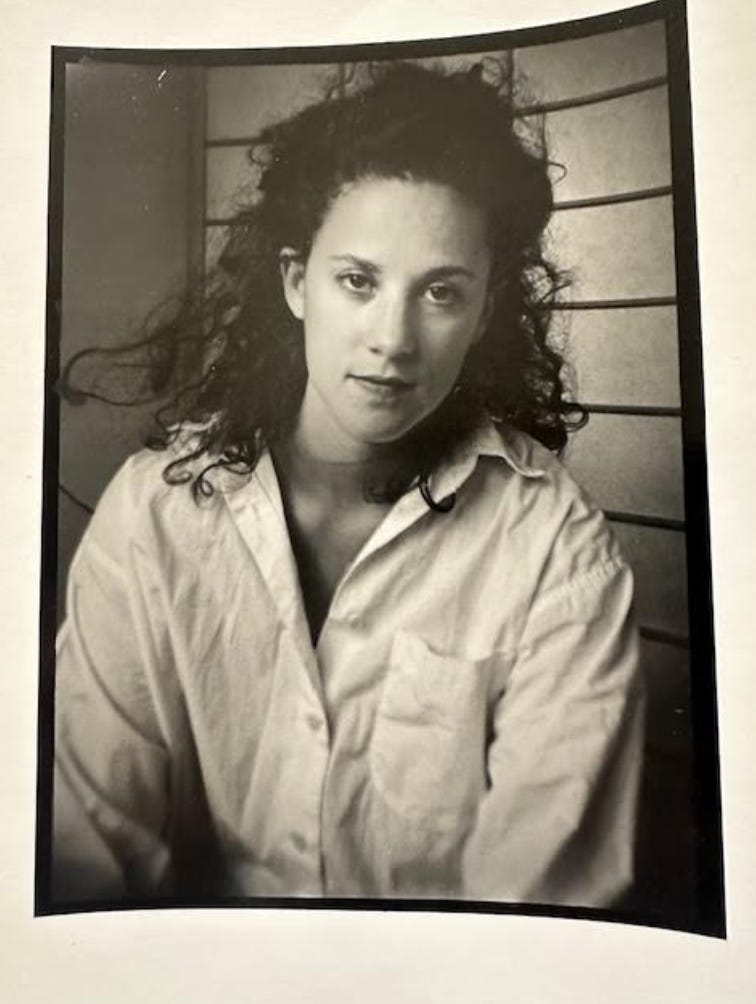

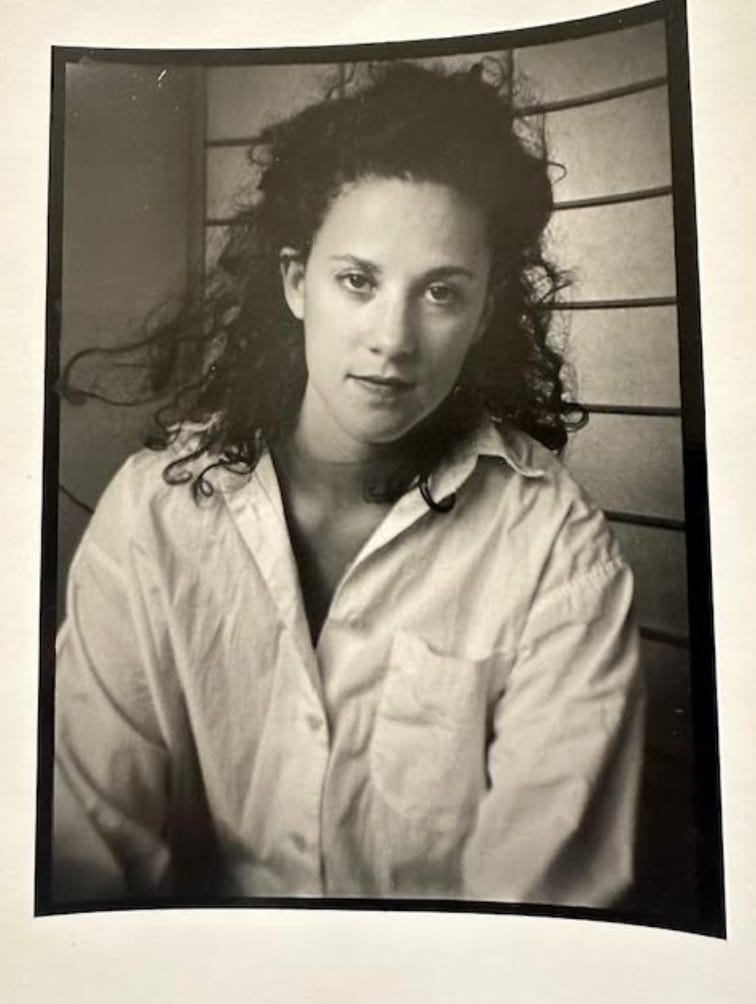

Spring, 1985

Toward the end of my sophomore year at Oberlin, my dad, age 48, was diagnosed with the cancer that would have him dead within the year. I got the news from my mom, who called my dorm room early on a Tuesday, hours before I would otherwise be awake (for years after this event, I would become terrified if my phone rang before 8 a.m., convinced that mortally bad news was on the other end of the line).

“Your father has a mass in his throat,” Mom said. “He’s having surgery next week. You probably want to come down to Houston and see him before then.”

A mass in his throat? What did that mean? I paused for a moment, still groggy, to puzzle it out. “So, he has cancer?” I finally ventured. My mother was of a generation that was brought up to avoid saying that word. I was pissed at her, in that moment, for choosing cagey phrasing and not giving it to me straight.

“Yes,” she replied, and then tried to say more but her voice broke and she started to cry. My parents had been divorced for years by then, and weren’t on especially great terms, so her crying was my first sign that this cancer might be of the super-bad kind.

I leaned against the dorm room wall where the phone hung, stared into the middle distance and let this new information sink in. My roommate was sleeping through all of this, and I was stunned, too stunned to cry. And my mother’s crying was making me impatient somehow. I got off the phone with her and then dialed my dad’s house, but the machine picked up.

Which was just as well. My dad and I were not close; it would be more accurate to call our relationship cordial but strained. He had, just a few years earlier quit the heavy drinking that had, among other things, driven a wedge between us, but still I struggled to find my footing with him. As a drinker, he had been outright mean, and that meanness was pretty effectively blunted by his sobriety. Still, we could never seem to get on the same foot.