BREAKFAST OF CHAMPIONS

We’re going two-for-one this week: here’s Chapter 10 of the book, and no paywall on this one…

Image: https://unsplash.com/@evitka

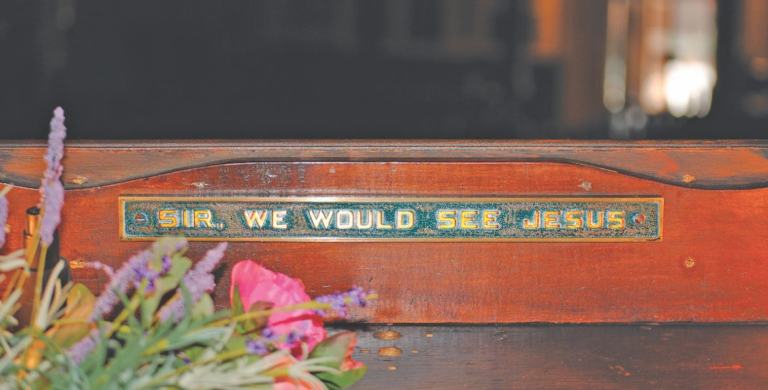

Foxes have holes, and birds of the air have nests, but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head. Matthew 8:20, ESV

In a poll for the Bible’s most popular figure, Bildad the Shuhite is unlikely to receive even one vote. With a name that sounds as suited to Game of Thrones as to Holy Writ, he barely registers in most people’s gallery of Old Testament heroes – yet he has an important role in the story of Job. He is one of three friends who, in three distinct rounds of conversation, present Job with their understanding of why he is suffering. In chapters 8,18 and 25, Bildad’s speeches reveal a negative and judgemental view of humanity, and of Job in particular. God always punishes the wicked, and Job is clearly being punished, so he must have done something to upset the Almighty. The climax of Bildad’s argument is his graphic description of the worthlessness of humans. He says, ‘How then can man be in the right before God? How can he who is born of woman be pure? Behold, even the moon is not bright, and the stars are not pure in his eyes; how much less man, who is a maggot, and the son of man, who is a worm!’ (Job 25:4-6, ESV).

It would be difficult to find images more degrading than maggots and worms to illustrate the humility of humans before God. Ben adam serves here as a pointer to this humble state. ‘Put not your trust in princes, in a son of man, in whom there is no salvation,’ the psalmist warns us, ‘When his breath departs, he returns to the earth; on that very day his plans perish’ (Psa. 146:4, ESV). And again, ‘O LORD, what is man that you regard him, or the son of man that you think of him? Man is like a breath; his days are like a passing shadow’ (Psa. 144:3-4, ESV). Isaiah draws on similar imagery, to ask ‘Who are you that you are afraid of man who dies, of the son of man who is made like grass?’ (Isa. 51:12, ESV). These are all ben adam references: this seems to be the phrase of choice when looking to emphasise the limitations of the human condition.

We should note that at the end of the drama, Bildad and his two friends are rebuked by God himself for having misrepresented his character (Job 42:7). The ‘worms and maggots’ view of the human condition is never endorsed by the text. All the same, Bildad demonstrates that while the phrase ben adam can be used as a simple designation of humanity, it can also go further, emphasising the weaknesses and humility of the humans in question.

There can be little doubt that this contributes to Jesus’ choice of title. Only once in the gospels does he attach adjectives to his own identity, when he describes himself as ‘gentle and lowly in heart’ (Matt. 11:29, ESV). ‘Gentle’ here is the same word used in the Beatitudes to describe ‘the meek’ – those who will one day inherit the earth. It denotes a person who is unpretentious and undemanding, not overly consumed by the struggle for status or the needs of their ego. ‘Lowly’ is something else. It’s a word that more often appears in our English Bibles as ‘humble’, but it doesn’t describe an attitude or a way of being: it denotes social status. This is the word Mary uses in her prayer before the birth of Jesus, when she rejoices that God has ‘brought down the mighty from their thrones and exalted those of humble estate’ (Luke 1:52, ESV).

Many commentators have suggested that Jesus’ self- description as meek and lowly connects not so much with Bildad’s ‘worms and maggots’ as with the Hebrew idea of the anawim, the blessed poor. Anawim is the plural form of the Hebrew word ānāw, variously meaning poor, afflicted, humble or meek. When Moses is described as ‘more humble than anyone else on the face of the earth’ (Num. 12:3, NIV), ānāw is the word used. In Psalm. 37:11 (NIV), we read that the meek (anawim) ‘will inherit the land and enjoy peace and prosperity.’ When Jesus suggests that the meek are in line for an even better deal, inheriting not just the land but the whole earth, it is likely that he has the anawim in mind. ‘The poor’ of Isaiah 61:1 and Luke 4:18 – to whom Jesus is anointed to proclaim the good news – are, once again, the anawim. In modern terms we might say ‘the destitute’ or ‘the oppressed’, or in some contexts ‘the disadvantaged’.

In Hebrew tradition, the anawim were virtuous and devout. These are people who have not come out as winners in the lottery of life, yet whose poverty has not produced bitterness but humility and modesty. They were the faithful ones who, more than any others, were waiting for the justice the messiah would bring. Jesus is identifying with ‘the lowest of the low’ in society. Like the hostess at a self-service buffet who places herself at the back of the line to ensure everyone else eats before her, his action in identifying with the least implies radical inclusivity. If these, the destitute, are drawn into his human identity, surely not one of us is left out in the cold.

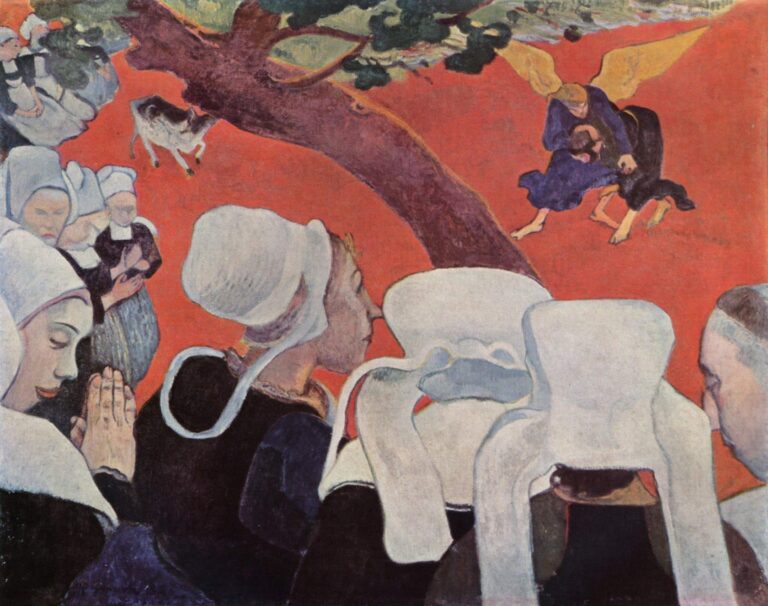

Jesus frequently associates the Son of Man title with images of human frailty. ‘Foxes have holes, and birds of the air have nests,’ he says, ‘But the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head’ (Matt. 8:19-20, ESV). He urges his disciples not to seek status, but to choose the humble path. ‘Whoever wants to be a leader among you must be your servant,’ he says, ‘and whoever wants to be first among you must become your slave. For even the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve others and to give his life as a ransom for many’ (Matt. 20:26-28, NLT).

Matthew is unafraid, in his narrative, to show Jesus experiencing the weakness associated with the human condition. He details an intriguing incident with an unfruitful fig tree, telling us, ‘In the morning, as Jesus was returning to Jerusalem, he was hungry, and he noticed a fig tree beside the road. He went over to see if there were any figs, but there were only leaves. Then he said to it, “May you never bear fruit again!” And immediately the fig tree withered up’ (Matt. 21:18-19, NLT).

There are definite overtones of an acted metaphor here, with God pronouncing judgment on the fruitlessness of unfaithful Israel. In Luke’s Gospel, a very similar story turns up in parable form (Luke 13:6-9), and the prophet Isaiah uses the ‘shrivelled fig tree’ (Isa. 34:4, NIV) as a symbol of God’s judgment.

Here in Matthew, though, the event doesn’t come about because Jesus is teaching – it comes about because he’s hungry. He is walking from Bethany to Jerusalem, a commute of just under an hour on foot. It’s early. Perhaps he didn’t have time for breakfast. He wants to eat a fig or two but is disappointed to find the roadside buffet closed. His reaction is swift and, to the casual observer, hot-tempered. He curses the tree: not for a season, but for life. You might even conclude that Jesus was hangry – that condition of human hunger that sours the mood and amplifies irritability. Doubtless, there are deep theological truths to be mined from this event – but there is also the self-evident reality: Jesus felt his hunger as deeply and as sharply as we would in the same situation. T. F. Torrance writes,

‘What overwhelms me is the sheer humanness of Jesus, Jesus as the baby at Bethlehem, Jesus sitting tired and thirsty at the well outside Samaria, Jesus exhausted by the crowds, Jesus recuperating his strength through sleep at the back of a ship on the Sea of Galilee, Jesus hungry for figs on the way up to Jerusalem.’

The gospels were written several years after the events in question when the exaltation of Jesus to the right hand of the Father was an acknowledged foundation of the Church’s theology. The writers, though, are unafraid to show us Jesus’ hunger and thirst. They want us to know that in entering the human condition, Jesus embraces the vulnerability integral to it. The letter to the Hebrews reminds us, ‘We do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathise with our weaknesses, but one who in every respect has been tempted as we are, yet without sin’ (Heb. 4:15, ESV). ‘In every respect’ because Jesus has indwelt and embraced in the fullest sense possible the reality of being human. The English Bible’s shortest verse, ‘Jesus wept’ (John 11:35, NIV) is a graphic reminder of how deep this indwelling was. If the first level of meaning to the phrase ‘the Son of Man’ is the bald statement ‘I am human,’ the second is the acknowledgement of the frailty inherent to that identity. All too often we miss the radical nature of this truth. That God should come to us in weakness – as frail as we are – is an idea that can tilt the universe.

Historian Tom Holland has written an influential account of the impact of the Christian movement on the forming of Western culture. He suggests that belief in Jesus effectively displaced the influence of ancient Greek and Roman cultures, to become the primary source of what most would recognise today as the values of Western civilisation. This is not unusual in itself – there have been many books written over the years that have charted the influence of ‘Judeo-Christian values’ on our democratic societies. What is different, though, is Holland’s account of why this is the case. He suggests that the specific aspect of the Christian movement that upended Greek and Roman dominance was its emphasis on the dignity and value of persons who are weak. He cites the apostle Paul writing to the Church in Corinth, ‘In a city famed for its wealth, Paul proclaimed that it was the “low and despised in the world, nothings” (1 Corinthians 1:27-28), who ranked first. Among a people who had always celebrated the agon, the contest to be the best, he announced that God had chosen the foolish to shame the wise, and the weak to shame the strong.’

This elevating of the weak produced a cultural revolution whose impact can be felt to this day. The root of this revolution – ground zero for the Christian movement – is the cross: an event that, for Holland, runs counter to the most profoundly held assumptions of Paul’s contemporaries – Jews, or Greeks. ‘It is the audacity of it,’ he writes, ‘the audacity of finding in a twisted and defeated corpse the glory of the creator of the universe – that serves to explain, more surely than anything else, the sheer strangeness of Christianity.’

It is significant in this light that Jesus so frequently associates the Son of Man title with predictions of his impending sufferings:

‘And he began to teach them that the Son of Man must suffer many things and be rejected by the elders and the chief priests and the scribes and be killed, and after three days rise again’ (Mark 8:31 ,ESV).

‘Let these words sink into your ears: The Son of Man is about to be delivered into the hands of men’ (Luke 9:44, ESV).

‘The Son of Man is going to be delivered into the hands of men, and they will kill him. And when he is killed, after three days he will rise’ (Mark 9:31, ESV).

The unexpected nature of these statements is evidenced in the reactions of his disciples. In one instance they don’t understand, and are afraid to ask him what he means (Mark 9:32, Luke 9:45). In another Peter rebukes him (Mark 8:32). In still another, the disciples respond to his predictions of suffering and humiliation by asking if they can perhaps have thrones alongside him when it’s all over (Mark 10:35-37, Matt. 20:20-21). They initiate a discussion about which of them is the greatest-of-all-time (Luke 9:46). All of which shows that in steering towards weakness, humility and suffering, Jesus is working against the prevailing culture and expectations.

Tom Holland’s account contrasts the life-affirming influence of the crucified Christ with the raw brutality of the ancient world. The ruling elites of the old empires were callous in their barbarity – especially towards the vulnerable or socially despised. Humble citizens had no choice but to accept the cruelty of their situation, slaves to the whim of their superiors. It would be centuries before the words ‘human’ and ‘rights’ would be brought together. Power belonged, by definition, to the strong, whose job it was to rule over, and if necessary eliminate, the weak – and these rules applied as much to gods as to emperors. Holland writes, ‘The notion that a god might have suffered torture and death on a cross was so shocking as to appear repulsive. …In the ancient world, it was the role of gods who laid claim to ruling the universe to uphold its order by inflicting punishment – not to suffer it themselves.’

The story of the Son of Man, as interpreted and enacted by Jesus, is a narrative of the victory of humility over power, placing the embracing of weakness at the very core of the incarnation. It bears mentioning again here that the Greek and Roman worlds were not against the deification of a human being as such. Some emperors were seen as gods when alive, while others were worshipped after their deaths. What doesn’t fit the dominant worldview is the exaltation and deification of someone as ordinary and obscure as Jesus. Like a down-and-out booking into the Presidential Suite, such a leap was considered both inappropriate and impossible. Status was everything, and divine status was reserved strictly for the

highest class of human beings. To name Jesus as both human and divine is to recognise the willingness of God himself to embrace the human condition at its weakest, even to the point of death. Humility is not an incidental by-product of the ministry of Jesus: it is the very heart of his vocation.

Thanks for reading… the book is available now on Amazon (Hardback, Paperback and e-Book) and on Apple Books.