People Are ‘Harmonizing’ Their Faces. Why?

Over the summer, millions of videos on “facial harmonization” and “facial balancing” collected billions of views across social media platforms.

Some users zoomed in on their wide eyes, plump lips, and defined jawlines — conventionally, Eurocentrically attractive features — only to zoom out and “reveal” that their various parts weren’t symmetrically aligned: “Good features, bad facial harmony,” they called it. Others shared close-ups of their hooded eyes, large noses, and thin lips, only to widen the lens and stun viewers. Surprise! They were better-looking than anticipated, thanks to symmetry! This phenomenon was known as “bad features, good facial harmony.”

The takeaway? Total perfection is futile pursuit!

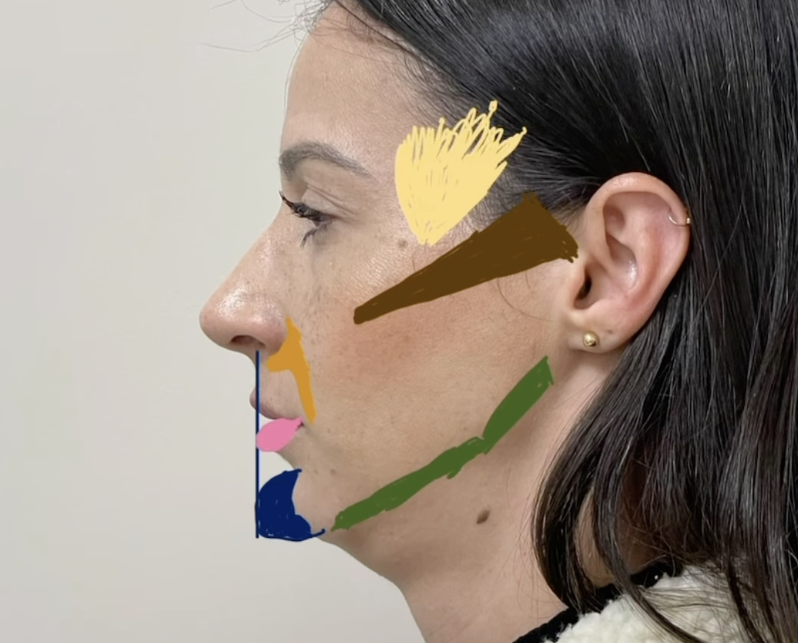

Just kidding. Rather than spotlight the absurdity of modern beauty standards, these posts have since yielded a fresh crop of how-to videos: makeup to counteract “high- or low-contrast” coloring, myofascial massage to lift brows into alignment, and rhinoplasties to “correct” jagged profiles (among other proportional horrors). One cosmetic injector details “balancing” her sister’s appearance with chin filler; it “helped her nose look a lot smaller,” she says. Another doodles new, proportional lips over pictures of her patients’ current, disproportionate lips to show how harmonization can “bring out the best version of you.” Many praise Lindsay Lohan’s recent (rumored) plastic surgery transformation for “creating harmony in her features.”

The trend has “definitely influenced the way patients approach their cosmetic goals,” agrees Dr. Usha Rajagopal, a plastic surgeon and the medical director of San Francisco Plastic Surgery and Laser Center, although the concept of harmony isn’t new to those in the field. It’s a foundational tenet of cosmetic medicine, she says.

But why? For all the people proselytizing the face- and life-changing power of harmony, it seems no one can explain what, exactly, makes it important — worth thousands of dollars, considerable pain and effort, or at least a sizable swath of brainspace — beyond repeating its definition. What I hear online: Harmony is “essential” because it balances. “Balance” is “a top priority” because it “enhances symmetry.”

“Symmetry within individual features — like the eyes, cheeks, and lips — is crucial because when these elements align well, they give the face a sense of proportion,” is Dr. Rajagopal’s answer. “On a larger scale, balance between features, such as the relationship between the nose and chin, is equally crucial. If one feature is out of proportion, it can draw attention to that area and disrupt the overall balance.”

This also amounts to tautology: Harmony is necessary because it harmonizes. It makes sense only if “harmony” implies more than mere self-reinforcement; if it carries meaning beyond itself.

When we want to harmonize our features, then, what do we really want?

Maybe it’s as simple as the TikTok trend suggests: We want to be seen as good. And we’re in luck! American society has the moral code of a Disney cartoon. Grown adults think Anne Hathaway looks youthful at 42 because she’s nice and Prince William went bald because he’s “problematic.” Facial harmonization fits right into this aestheticized, easy-bake take on ethics. Here, to ascend into the realm of heaven (fame, fortune, or a sizable Instagram following), you need not be a good person — just one with “good harmony.”

The association makes sense if you squint. Beauty has been linked to concepts of harmony and spirituality for centuries. In Greek mythology, Harmonia, the goddess of harmony, is the daughter of Aphrodite, the goddess of beauty. Harmony is considered a virtue almost every religious system, from Western faiths like Christianity and Islam to Eastern philosophies like Taoism and Buddhism, and cosmetic nurse Vanessa Lee claimed to “address the face through the Eastern tradition of balance and harmony” when she coined the term “facial balancing” in 2017.

Harmony entered the realm of the body long before that, though. And it entered through pseudoscience.

Consider the 18th-century theory of the “facial angle,” developed by Dutch physician Petrus Camper. In order to establish a continuum from animals to humans, Camper measured the facial angles of Black, Asian, and European people and compared them to those of orangutans. His work helped legitimize racial hierarchies used to justify colonialism, slavery, eugenics, genocide, and general dehumanization — as well as the beauty standards that accompany them. (As Sam Kriss put it in his recent piece on political vibe shifts, “The hot girls are getting into the skull-measuring type of racism.”)

Researchers linked asymmetrical features to insanity in the 19th century, writes Moshtari Hilal in Ugliness, while failing to notice “how lopsided their own faces were.” (Asymmetry is standard in 98% of the population.) Italian physician Cesare Lombroso theorized “the nature of the criminal” around the same time, and claimed that thieves had “crooked” noses — a stereotype that still informs the “Western image of evil” today. See: the trope of the “sinister schnoz.”

These (false) findings echoed through pre-Nazi Germany as doctors “catalogued Jewish skin tone, hair color and structure, and nose shape [to] lump Jews together with ‘races’ that were already deemed inferior within the colonial worldview,” Hilal explains.

Harmony symbolized supposed biological superiority. (Ahem. Is it a surprise that facial balancing is trending in Trump’s America, as far-right ideology gains momentum across the world?) When the modern nose job was popularized in pre-war Berlin, it promised patients “a degree of invisibility [that] would liberate them” from discrimination, as Hilal puts it. Well, at least from some discrimination.

For all its focus on proportionality, facial harmonization has an outsize hold on a specific subset of the population: women. It’s Feminism 101! “Women are mere ‘beauties’ in men’s culture so that culture can be kept male,” Naomi Wolf writes in The Beauty Myth, and physical beauty is “inert” — a quality not found in people, but objects.

The beauty industry tends to frame women as the particular object of the artwork — a canvas for expression, clay to be sculpted. Plastic surgeons like Dr. Rajagopal even rely on the “rule of thirds,” a concept initially introduced in the late 1700s to guide the harmonic composition of paintings, to “create the best possible balance for each patient.”

Dr. Rajagopal describes “assessing the front view” of her patient’s faces and “evaluating the upper, mid, and lower face to determine if any areas like the chin, jaw, or cheeks need attention.” Should a particular third or feature stand out, “it means the balance has been disrupted,” she said. “In those cases, I feel I haven’t done my job, as true facial harmony should be subtle and seamless, enhancing the face without drawing attention to individual features.”

This is not how the rule of thirds is meant to work. In the art world, the technique is “a way to draw your viewer in and keep them engaged,” says Jonquil O’Reilly, an Old Master Paintings expert at Christie’s. Harmony isn’t “necessarily about symmetry,” she continues. “You can create ‘balance’ in different ways, through negative space, for example.” The end goal isn’t seamlessness, but tension and interest.

It follows that facial balancing is less about harmony than homogeneity; the mass-production of blank canvases more than masterworks.

There is, of course, always the argument that human beings are inherently drawn to the golden ratio of 1:1.618 — a mathematical equation found in nature, one associated with the Fibonacci sequence. Artists like Leonardo Da Vinci have used it for centuries to create balance in their work, and it’s widely considered the pinnacle of harmony and beauty. (Bella Hadid’s proportions hew close to the golden ratio, for example.)

It’s science, one might say. It’s objective! It’s… not. A recent study published in the Korean journal Maxillofacial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery concluded that “there is no convincing evidence that the golden ratio is linked to idealized human proportions or facial beauty.”

The same platforms popularizing facial harmonization have effectively debunked the golden ratio’s universal allure, anyway. In 2024, Dr. Neelam Vashi, an associate professor of dermatology at Boston University’s medical school, noticed more patients requesting perfectly even lips when getting filler, rather than the accepted standard (a more prominent bottom lip). Curious, she studied the phenomenon on a global scale. After poring over Instagram posts, she’s determined the perceived ideal has indeed shifted from 1:1.618 to 1:1.

“That aspirational symmetry we’ve all wanted for centuries,” Apple News In Conversation reports, “social media has upended in just a few years.”

Harmony, then, is not a fixed measurement. It’s a social and historical construct, one that changes over time, accumulating layers upon layers of meaning; layers that get embedded in our collective and individual subconscious, influencing how we interpret and react to the world, even if we can’t quite articulate our reasons. Beauty culture’s current preoccupation with harmony is not only about balance and symmetry — it’s about who gets to be seen as good or bad, as superior or inferior, as human or animal or object.

And really, that’s too much to hang on a face. It’s bound to cause some sagging.