Plumpgasm Nudegasm

The dress code for Monday night’s Met Gala was “Tailored For You,” inspired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art Costume Institute’s newly unveiled exhibit Superfine: Tailoring Black Style. I was curious to see how attendees would interpret “tailored” in terms of beauty — because what is the flesh, really, if not a suit already tailored to you? The singular, literal creation of your genetics, environment, experiences, lifestyle?

While I think the “untouched” look would’ve been a spot-on (and press-worthy!) interpretation of the theme, no one went there. Instead, some spent six figures on face and body prep alone. Tailoring the body to meet the Met Gala’s standards of presentation, then, can cost 900% more than tailoring a Met Gala gown to fit the measurements of the body (around $10,000) and 33% more than a Met Gala ticket ($75,000). Absurd!

Also absurd: the flood of press releases that hit my inbox this week explaining exactly how to recreate guests’ red carpet glam, step-by-step and product-for-product — “Get The Look” being the antithesis of “Tailored For You.” (I wonder whether the style of the Black dandy, as described in Monica L. Miller’s 2009 book Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity, which traces the his “emergence in Enlightenment England to his contemporary incarnations in the cosmopolitan art worlds of London and New York” and informed the Met exhibit, could have flourished as it did in the era of click-to-buy consumerism…)

Ahead, a non-exhaustive list of inanities from these off-theme, post-Met marketing ploys — along with the beauty looks I (surprise!) loved.

I suspected a makeup brand might turn “Tailored For You” into a promotion for some new shade-matching foundation technology, and L’Oréal came close by partnering with Laura Harrier to debut Skin Ink, a “revolutionary all-new foundation concealer hybrid powered by cutting-edge science.” The product name suggests Skin Ink is meant to mimic the effects of semi-permanent facial tattooing, a procedure meant to mimic long-wear foundation, itself a product meant to mimic skin. Here, all that’s human is removed from the cycle of inspiration — the foundation replicates tattooing which replicates foundation which replicates tattooing, etc. — and yet, with this PR push, L’Oréal hopes consumers will want to mimic Harrier’s skin (which is mimicked by a foundation, which mimics the effects of semi-permanent facial tattooing, and so on and so forth).

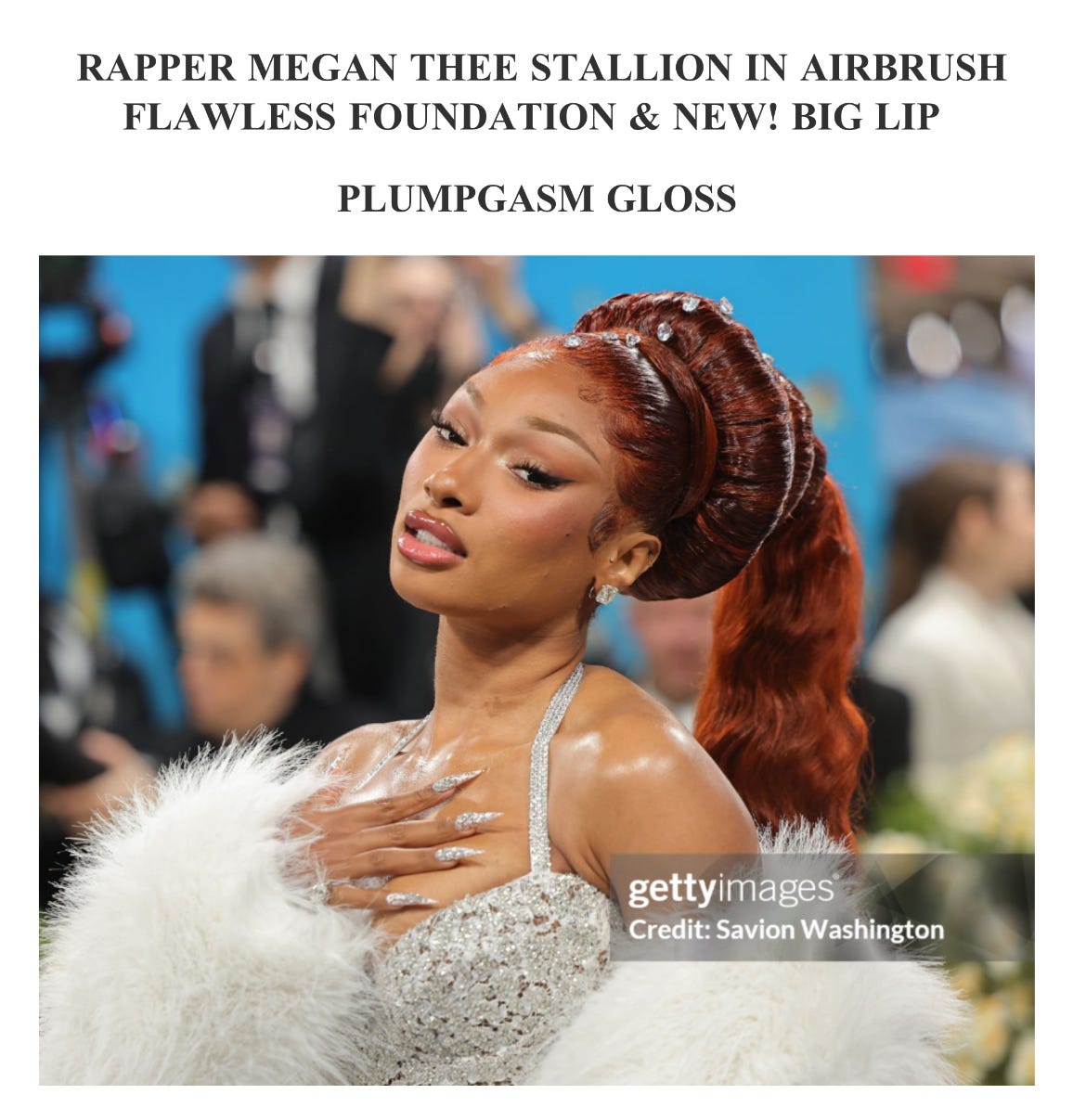

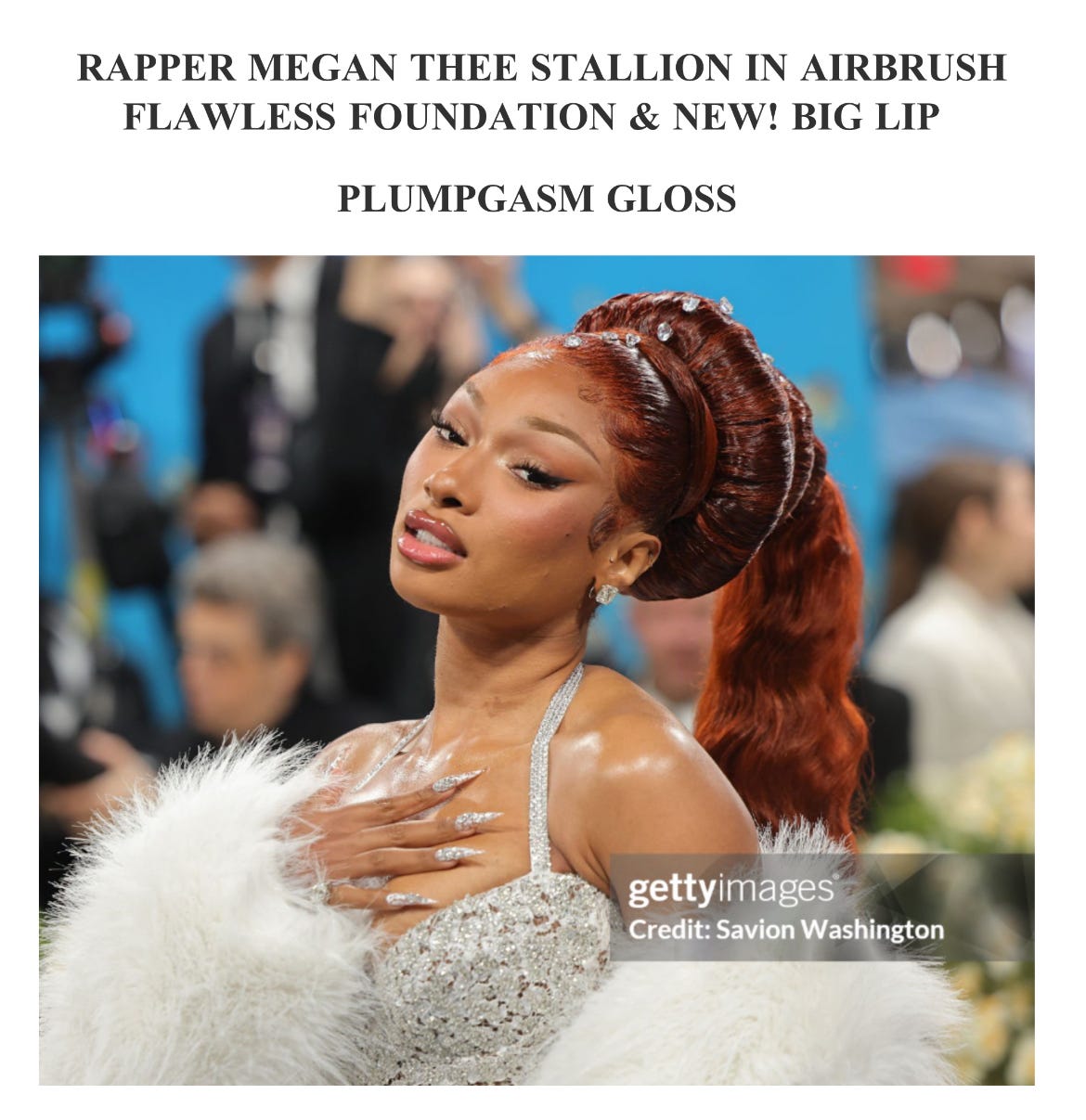

Eurocentric beauty culture has a long history of co-opting Black features for profit. The widespread “adoption of a racial aesthetic,” including “surgically enhanced full lips and big asses,” Robin M. Boylorn wrote for Slate in 2020, “reiterates the ways cultural Blackness is celebrated while embodied Blackness is denigrated.” Embodied Blackness is further denigrated in marketing which suggests the very features informing today’s beauty standard are nonetheless never enough; big lips, for example, could and therefore should always be bigger (although this message is usually laundered through the language of “enhancing what you’ve got” or meeting some other measure of beauty, such as the “plumpness” or “fullness” of youth). This history came to mind when I opened Charlotte Tilbury’s Met Gala Get The Look email to find an image of Megan Thee Stallion under the words “BIG LIP PLUMPGASM GLOSS.” Plumpgasm, a portmanteau referencing lips so plump as to be orgasmic, also hints at the rampant fetishization of racialized features. It’s a relevant choice — perhaps unintentionally, on Charlotte Tilbury’s part — for a night celebrating how Black dandies “subvert and fulfill normative categories of identity” through style, if not an ideology I want to add to cart.

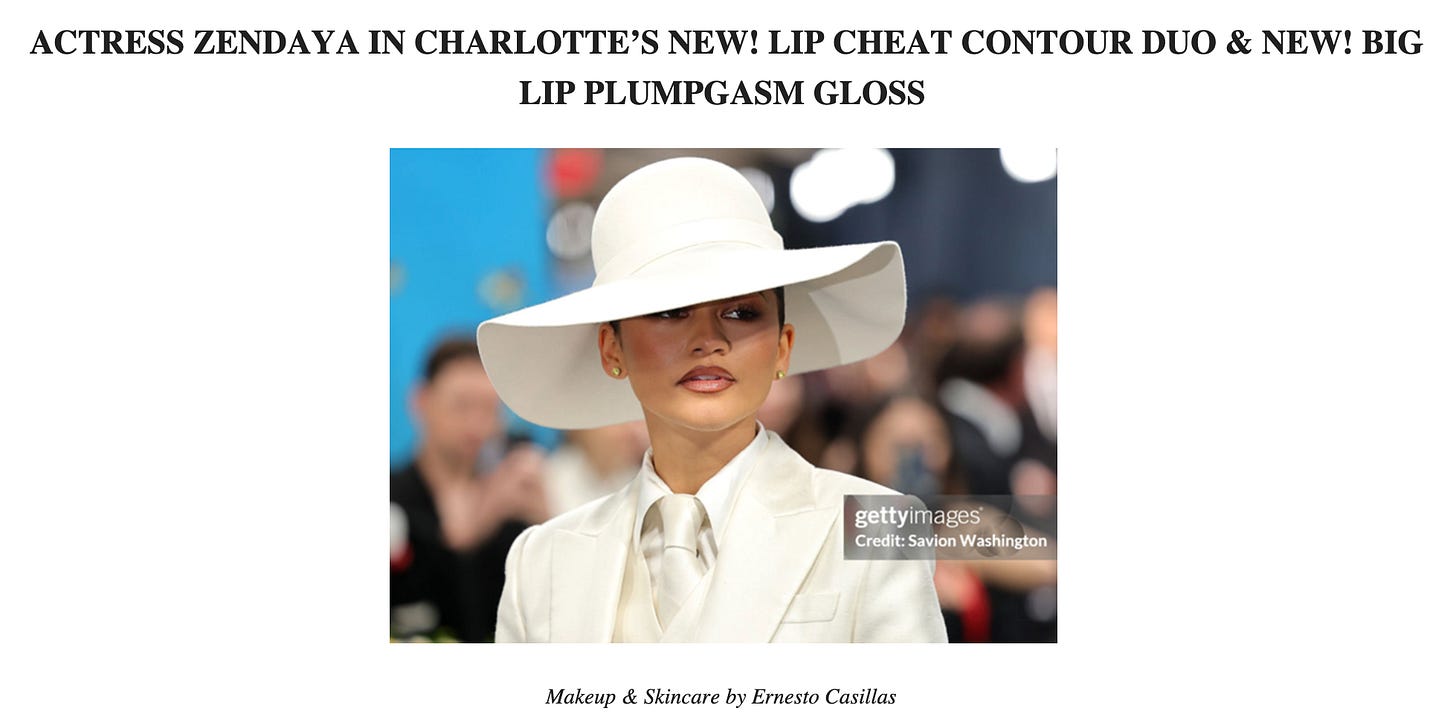

Zendaya also wore Charlotte Tilbury Big Lip Plumpgasm Gloss to the Met Gala. Shade name: Nudegasm Diamonds. I’m reading John Berger’s Ways of Seeing right now, so this immediately made me think of his take on the nude artwork: “To be naked is to be oneself,” Berger writes. “To be nude is to be seen as naked by others and yet not recognized for oneself. A naked body has to be seen as an object in order to become a nude. (The sight of it as an object stimulates the use of it as an object.)” In Berger’s analysis, nude paintings center the erotic experience of the viewer rather than the subject. I think this could apply to the nude lip as well: The lip’s nakedness is made nude through the object of the lip gloss, which then turns the lip into an object (a sight), which stimulates the use of the sight as yet another object (an ad). The “gasm” doesn’t belong to the wearer; it literally belongs to the seer, who the brand converts into a buyer.

“For this year’s Met Gala, Sabrina and I … were going for a perfectly lived-in vibe,” said Sabrina Carpenter’s Redken colorist, Laurie Heaps. The process required eight steps, nine products, and a finishing blast of Redken Max Hold Hairspray — so as not to let living interfere with the illusion of it, naturally. It’s hyperreality for hair: The simulacrum replaces the real as the ideal, and “lived-in” becomes shorthand for an aesthetic detached from living (responding to stimuli) and dependent on dead labor (commodities).

If Carpenter is an example of effort sold as effortlessness, Walton Goggins is an example of effortlessness sold as effort. His stylist, Ermahn Ospina, said he wanted to create an “unexpected” look for the Met Gala. What’s unexpected is not Goggins’ hairstyle — which looks roughly the same as it did when he played a “rugged and greasy-haired” character on the White Lotus earlier this year — but the work that went into it: $258 worth of Moroccanoil products, including shampoo, conditioner, detangler, volumizing mist, volumizing mousse, texture spray, texture clay, and hairspray.

Completing the trifecta of hair-related absurdity, Parfums de Marly sent out a PR blast for a $93 hair perfume, which was supposedly worn by Tyla and Joey King on the red carpet (although there’s no way to tell). It’s the epitome of a nonsense (“non-sense”) sales pitch: Potential consumers can’t see or smell the product’s effects before they purchase; it’s enough to know a celebrity did.

Keys Soulcare circulated a Get The Look blog post after the Met Gala, replete with links to the exact skincare and makeup founder Alicia Keys used that night. “Alicia Keys’ makeup looks are all about embracing your light,” it reads. Sure! But it seems her marketing is more about erasing your (perceived) imperfections: The images in the post appear to be edited, or maybe strategically uploaded in low resolution, to blur and obscure the blemishes on her chin — and thus, I’m assuming, more effectively sell her products. Capitalism corrupts!

Doja Cat’s glam was my favorite of the night. “We wanted to channel the surreal elegance of a hand-drawn sketch — something both animated and architectural,” said makeup artist Pat McGrath. Together they opted for lavender eyeshadow and red lipstick, a combination often used in animation to signal femininity (see: the dancing fish in Fantasia, Jessica Rabbit, Greta Gremlin). This quality of “animatedness” is also theme-appropriate; in Ugly Feelings, critic Sianne Ngai describes the aesthetic as an “exaggerated emotional expressiveness” that “whether marked as Irish, Jewish, Italian, Mexican, or (most prominently in American literature and visual culture) African-American … seems to function as a marker of racial or ethnic otherness.” Cultural representations of Black “liveliness, effusiveness, spontaneity, and zeal,” she writes, have historically been used to reinforce “the notion of race as a truth located, quite naturally, in the always obvious, highly visible body.” Incorporating this critique into Doja’s look — and highlighting animation as artifice — echoes the Black dandy’s tradition of reclaiming and reinterpreting “limiting identity markers” through style, as “a gesture of self-articulation.”

The rest of my favorite Met Gala looks — Megan Thee Stallion’s updo, Sha’Carri Richardson’s hair bows, Lupita Nyong’o’s bejeweled brows, Torkwase Dyson’s hand and nail art — similarly use cosmetics to adorn/decorate the body rather than “correct”/”perfect” it, and in this way, I think, resist easy commercialization. If correction implies a standard you can click to buy, adornment refuses one.