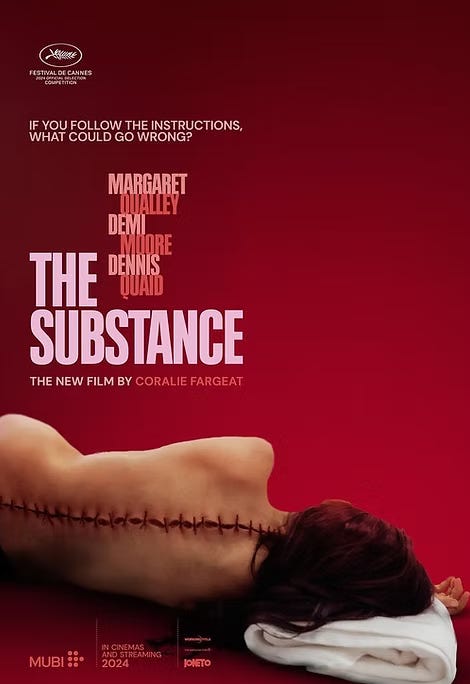

‘The Substance’ Is A Fairy Tale (But So Is Beauty)

I liked The Substance, and I agree with almost every critic who didn’t like The Substance.

The characters are one-dimensional, they say. Writer and director Coralie Fargeat gives the protagonist, Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore) — a once-beloved actress who’s fired from her Suzanne Somers-esque aerobics show upon turning 50 — no raison d’etre beyond her role as the protagonist. Elisabeth has no interiority, no personality, no conversations, no friends; none of the complexities of a real-life human being.

Neither does Elisabeth appear to have motivations or hopes or dreams, other than the shallow and abstract motivation to be “better” and “younger” and “perfect.” These are the promises of the titular substance, a black-market drug that, when injected, allows Elisabeth’s body to birth a younger version of itself, Sue (Margaret Qualley). The doppelgängers must alternate consciousness every seven days to maintain results.

The script barrages the audience with the same repeated phrases — Remember you are one, Respect the balance, You can’t escape from yourself — to reinforce its point. As Sue disrespects the balance and Elisabeth absorbs the consequences, viewers are subjected to a seemingly gratuitous spectacle of gore, blood, and butchery. It’s over-the-top, heavy-handed, exaggerated.

These criticisms are correct. They aren’t flaws in the story, though, but elements of its design. The Substance is a fairy tale.

In her 2010 essay “Fairy Tale Is Form, Form Is Fairy Tale,” Kate Bernheimer writes that most fairy tales share four traditional elements: flatness, abstraction, intuitive logic, and normalized magic.

The characters in a fairy tale are “always flat,” according to Bernheimer, “whether Little Red Riding Hood, Stepmother, Hedgehog, or Beast.” Like Elisabeth Sparkle, they’re “silhouettes, mentioned simply because they are there.” This lack of psychological depth on the character level “allows depth of response” from the viewer. The audience can more easily project themselves into the story, which I think is evident in both defensive criticism (“Couldn’t be me”) and empathetic praise (“I feel seen”) of The Substance.

Flatness goes hand-in-hand with abstraction. “Not many particular, illustrative details are given,” says Bernheimer. “The things in fairy tales are described with open language: Lovely. Dead. Beautiful.” Or: Better. Younger. Perfect. The power of the fairy tale relies on this “deceptively simple” storytelling technique.

The intuitive logic of fairy tales or, in Bernheimer’s analysis, their “nonsensical sense,” is also prevalent in The Substance. One thing follows another without explanation. The audience doesn’t know who manufactures the Substance, who pays for it, what the active ingredient is. The cosmetic technology works only because it must in order to move the movie forward. “This … quality is also a sort of violation, a violation of the rule that things must make sense,” Bernheimer writes. It makes for “a story that enters and haunts you deeply.”

In the fairy tale’s world of normalized magic, “the magical and the real coexist.” In the mirror world of The Substance, the very real violence that the beauty industry enacts on the body manifests in magically violent ways, including the spine-defying birth of Sue, the unsurvivable desecration of Elisabeth’s body, and the merging of the two into Monstro Elisasue.

And then, of course, there’s the moral. Here The Substance takes on the dissociative doubling that beauty culture demands: the person versus the commodified appearance, the flesh-and-blood versus the filtered photograph, the surveilled versus the self-surveilling, the current you versus the so-called “real you” (the thinner you of the future, the younger you of the past). If the pursuit of beauty splits people into an actual self and an idealized self — and positions the sublimation of the former into the latter as the point of it all — The Substance cautions, Remember you are one. Respect the balance. You can’t escape.

Since its premiere, viewers have debated whether or not The Substance can be called “feminist.” I’d like to propose that it is indeed a feminist fairy tale, in the earliest sense of the phrase.

The term “fairy tale” comes from “a coterie of 17th century French female writers known as the conteuses, or storytellers,” Melissa Ashley reports in The Guardian. “French society had become dangerously religious and conservative” in the final years of Louis XIV’s reign, and “women’s lives … were deeply constrained.” Girls were married off as teenagers and kept from ever earning their own money, controlling their own inheritances, or divorcing their husbands.

Fairy tales served as a form of feminist consciousness-raising. The stories, often told in literary salons, were for adults. They reflected the conditions of women’s oppression and used “exaggeration, parody, and references to other stories to unsettle the customs and conventions that constrained women’s freedom and agency,” Ashley explains.

The Substance does this too, although its reflection of the conditions of women’s oppression has been repeatedly mistaken for endorsement. In The Cut: “The process of aging naturally is disgusting, this movie seems to be saying, and of course the audience agrees.” Well, no. The movie is saying that beauty culture frames the process of aging naturally as disgusting, and exaggerates this to inspire the audience to question its agreement. In Forbes: “It’s been a long time since I’ve watched a film that lingered so long on the alluring bodies of beautiful naked women.” Well, yes. The Substance parodies this with close-ups of men’s bodies — wrinkled foreheads, large pores, yellowed teeth ripping into flaccid shrimp; so untamed next to Sue’s smooth, toned glutes — to highlight the normalization of women’s objectification (not only on camera, but in their own lives, via cosmetic upkeep).

Fargeat continues in the French tradition by referencing other fairy tales throughout: The countdown to midnight before the bloody explosion of Elisasue is a Cinderella moment. The yellow coat shared by Elisabeth and Sue recalls Little Red Riding Hood. And the in-movie promo for the Substance itself mimics the most ubiquitous fairy tale of our time: the advertisement.

In her essay on form, Bernheimer predicted that “a continued underestimation of the techniques of fairy tales and their influence [will lead] to their disappearance.” I’m of a slightly different mind: Continued proof of their power has disappeared them into ads. It’s the logical conclusion of decades of deliberate watering down, of diluting their capacity to disrupt; what the Brothers Grimm “sanitized” and Disney “commercialized,” cosmetic companies later commodified. Modern beauty marketing retains all four markers of the traditional structure — flatness (the blank-enough model or celebrity spokesperson), abstraction (“Easy, Breezy, Beautiful!”), intuitive logic (the “science” of skincare, which always collapses with adequate explanation), and normalized magic (the promise of transcendent transformation) — with none of, to borrow a phrase, the substance.

“Have you ever dreamt of a better version of yourself?” asks the disembodied voice of the Substance ad, while Elisabeth watches footage of cells morphing and multiplying under a microscope. “Younger? More beautiful? More perfect? One single injection unlocks your DNA, starting a new cellular division.” It could easily be a spot for retinol, or CoolSculpting, or a Mommy Makeover, or wrinkle-relaxing neuromodulators. “I want[ed] to take that leap and do something for myself,” as one model, Kim, explains in a 2023 Botox commercial. “I’m the same old Kim, with fewer of those deeper lines.”

Elisabeth — lulled by form, steered by circumstance — buys in, of course.

Critics’ reaction to this plot point often amounts to, Who would do this? “Why would I take a drug that gives me a younger, more beautiful and fit body for a week if I didn’t get to experience the benefits myself, and only the bad side-effects after?” the Forbes reviewer writes. But people do this all the time. We do it with retinol, known to trigger dermatitis, a condition that spurred my own body horror-esque spiral in 2015. We do it with CoolSculpting, the popular fat-freezing treatment that left model Linda Evangelista “disfigured” in 2022. We do it with Mommy Makeovers, a series of post-childbirth plastic surgery procedures, complications from which killed “Wild ‘N Out” star Jacky Oh in 2023. We do it with neuromodulators like Botox, which have inspired tens of thousands of users to form online support groups to discuss the potentially life-altering side effects they believe they’ve experienced. Hope for a happy ending almost always obscures the reality of harm.

I doubt The Substance will change this — not because of its failings as a fairy tale, but because the beauty industry has co-opted the fairy tale so completely. It’s already co-opted The Substance, defanging the film’s criticism by acknowledging it, absorbing it, and ultimately overpowering it.

While the 2025 Oscars celebrated The Substance with five award nominations, the Oscars’ nominee gift bag included a $25,000 gift certificate for liposuction, and the Oscars red carpet showcased an “eerie” level of physical perfection, courtesy of the very injectables the film satirizes (Botox for wrinkle reduction, Sculptra for collagen production, and Wegovy for weight loss, among others).

After The Substance stocked Elisabeth Sparkle’s bathroom cabinet with Charlotte Tilbury skincare, perhaps in a nod to the brand’s over-the-top marketing of “magic” ingredients and official collaborations with Disney, Charlotte Tilbury sponsored Moore’s Oscars glam. Her final look featured 29 products, including the Magic Serum Crystal Elixir — the “SUPERCHARGED secret to your skin’s best future!” thanks to a “magic matrix of ingredients” — and Hollywood Flawless Filter Skin Tint, all of which were listed on Tilbury’s Instagram, accompanied by a clearly retouched image of Moore and a link in bio to purchase.

Wellness brand Sakara posted a promo for its Daily Elixir that night, describing it as “like ‘the substance,’ but legal, effective, and 100% not scary at all.” Ulta aired a mid-ceremony commercial claiming that “beauty is about possibilities.”

In the end, these ads capture consumers’ imaginations in a way The Substance cannot. Better, younger, perfect will always be more compelling possibilities (if less realistic) than dermatitis, dysmorphia, death. Beauty is our favorite fairy tale, and “fairy tales work on all of us,” as Bernheimer says. We can’t escape.

I spoke more about The Substance as a fairy tale back in November on the podcast with . Listen here: